L'AQUILA, Italy — In 2009, one of the deadliest earthquakes in recent Italian history hit the central Italian town of L’Aquila. A few days later, Eugenio Coccia, then director of the nearby Gran Sasso National Laboratory, the world’s largest underground laboratory for particle physics research, sat at his desk in a building that had escaped the devastation, and pondered.

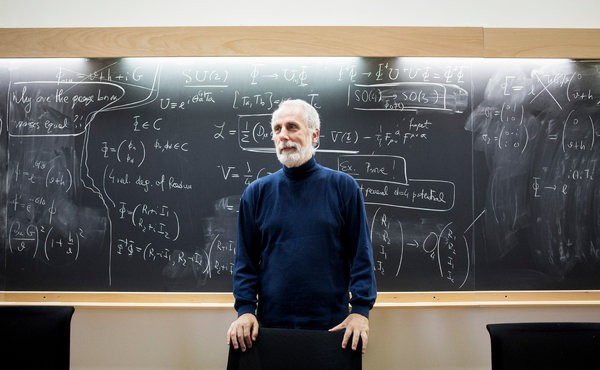

Gianni Cipriano for The New York Times

L’Aquila, Italy, which was severely damaged by an earthquake in 2009, is now home to a new institute for advanced studies.

Who would ever want to work or study in L’Aquila again?

Dozens of buildings had collapsed and 309 people — including 55 university students— had died in the quake. Mr. Coccia feared that the cultural damage to the city would be even more lasting than the architectural loss, he said in an interview.

That same day, he and a few colleagues started thinking about the strategy that, in the 1970s, had created one of Italy’s top schools of higher learning, the International School for Advanced Studies, in Trieste.

The northeastern region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia had used funds allocated for its reconstruction after a devastating earthquake in 1974 to build a prestigious science institute that had helped to transform Trieste into a European research hub.

That was what L’Aquila needed, Mr. Coccia and his colleagues decided: a research institute that would attract students from all over the world — and in the process revitalize the city.

In November, four and a half years after the earthquake, L’Aquila inaugurated its international center for doctoral and advanced studies, the Gran Sasso Science Institute, or G.S.S.I.

“Without the earthquake, this project would simply not have been possible,” Mr. Coccia, now the institute’s director, said in an interview in the school’s headquarters, a recently renovated 1930s palazzo just inside the city walls. “We thought it was the best way to respond to such a natural catastrophe.”

Selected by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the association of free-market democracies, among several projects designed to relaunch the city, the school has been funded partly by the Italian government and partly by the European Union.

One of five schools for advanced studies in Italy, it will operate under the supervision of the Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics, with a guaranteed budget for three years. After that, in 2016, it will be formally evaluated by Italy’s university and research review agency to determine its future status and funding.

The two-month-old school offers interdisciplinary courses in physics, math, computer science and urban sciences. For its first-year intake of 36 Ph.D. students — 14 of them foreign — L’Aquila has two major advantages: its direct link to the Gran Sasso laboratory, famous for its neutrino and dark matter experiments in caverns deep beneath the Apennine mountains, where students will be able to work; and its location in a city that is itself an experiment as it struggles to recover from the earthquake.

“This is an enormous open-air laboratory,” said Pietro Verga, 29, a former visiting scholar at City University of New York’s Center for Community Planning and Development, and now a doctoral student in urban studies at the Gran Sasso institute. “I wanted to come in the hope that we can help assess the redevelopment process with our technical skills. The city really needs it.”

“The scientific curriculum and the conditions were very attractive,” said Axel Boeltzig, a 25-year-old physics student from Germany. “But the lab so close by really was the big plus, if you plan to do experiments in Europe’s largest underground facilities, like me.”

“Here, you don’t just get to work in the lab for a few weeks; as of the second year, we can go more independently,” he added. “Many of our lectures are given by researchers who work there. You can talk to them, you have very close contacts to them and you can figure out together what issues you might want to work on yourself. For someone like me who likes the hands-on work, it was a great opportunity.”